A Circular Economy

Not a moment to waste |

10 years in transition

This is the timeframe that the Queensland Government has set itself to transition into a circular economy framework.

In 2022, all levels of government, multiple peak waste management and recycling industry bodies, and many key private industry entities involved in waste management and recycled materials came together to discuss 10-year plans for:

- organics management approaches and solutions,

- product stewardship programmes,

- waste bans both already implemented and upcoming and of course,

- policy development to assist public and private entities transition towards a circular economy.

Transitioning Queensland to a circular economy by 2032 is an ambitious goal, and not without its challenges, but certainly within the realm of possibility.

The primary focus of both government and industry is to improve Queensland’s resource recovery efforts by both local councils and industry. To that end, Queensland has set targets for resource recovery by 2050 of:

- 25% reduction in household waste

- 90% of waste recovered that does not go to landfill

- 75% waste recycling rates across all types

These targets, however, are integral to the establishment of a circular economy by 2032. Below, we’ll discuss key processes and industries that will move Queensland towards that goal.

What is a 'Circular Economy'?

In simple language, the term ‘circular economy’ is used to describe an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design. It means eliminating waste and finding options for the continual use of resources.

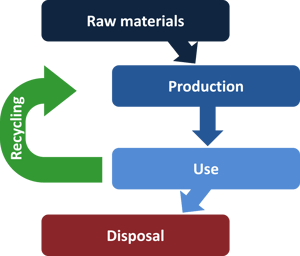

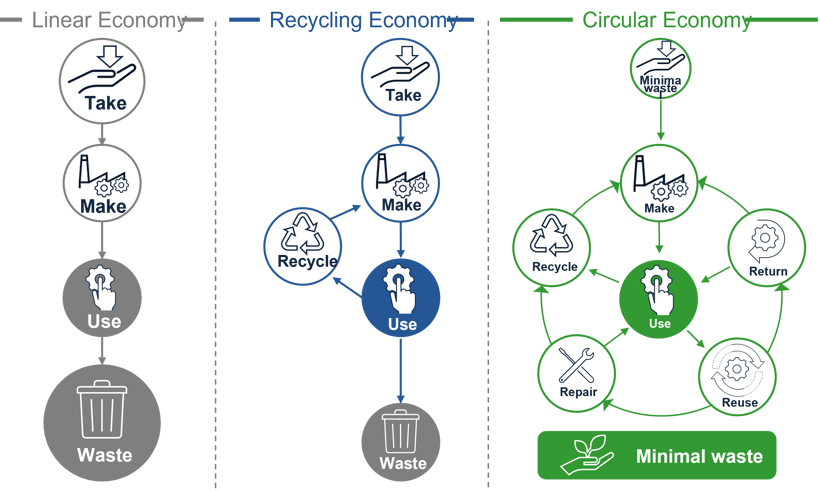

In perspective, traditionally society has operated according to what is termed a linear economy.

|

“The last 150 years of industrial evolution have been dominated by a one-way or linear model of production and consumption in which goods are manufactured from raw materials, sold, used and then discarded or incinerated as waste” [World Economic Forum] |

With growing societal environmental consciousness, over the past few decades, we have transitioned towards a recycling economy.

This model places greater emphasis on the recycling of materials but still generates large amounts of waste as only particular waste streams have been considered for recycling, typically, metals and select plastics.

[Image Source: Reuse/Recycling Economy: Researchgate]

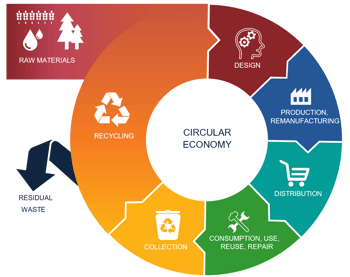

A circular economy is the evolution of the recycling economic model into a more progressive and inclusive model where all waste is treated as a resource and the only true waste is a product that has no meaningful further use.

As practice and technology improves what is considered ‘of no further meaningful use’ will also change.

“A circular economy is an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design. It replaces the end-of-life concept with restoration, shifts towards the use of renewable energy, eliminates the use of toxic chemicals, which impair reuse and return to the biosphere, and aims for the elimination of waste through the superior design of materials, products, and systems and business models”

[World Economic Forum]

[Image Source: Circular Economy Flow Diagram: CSIRO]

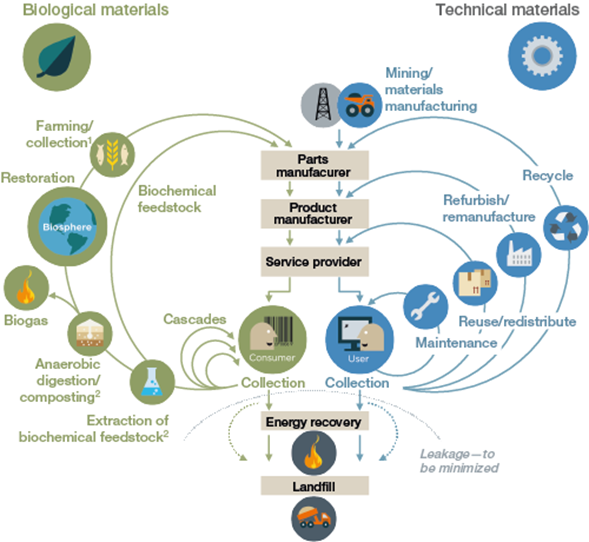

Detailed Circular Economy Flow Diagram [Source: World Economic Forum]

Detailed Circular Economy Flow Diagram [Source: World Economic Forum]

Advantages of a circular economy include;

Discussions around current waste recycling and recovery statistics, policy progress and practices, challenges and barriers to entry are topics of considerable detail. However, three tools of particular interest to industry to assist in moving towards a circular economy that emerged from the conference were;

|

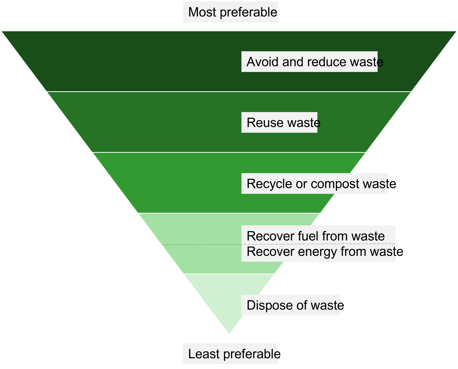

A circular economy follows the principles of the waste hierarchy.

[Image Source: Waste hierarchy: Qld Government] |

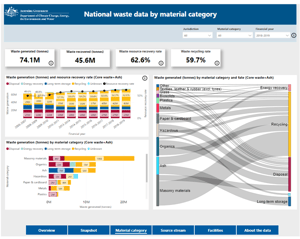

Waste and Resource Recovery Data Hub - National Waste Data Viewer

The National Waste Data Viewer visualises the data in the National Waste Database 2020. It shows yearly trend information and is filterable by state, waste stream and financial year. Its purpose is to make data more accessible to industry, governments, councils and the public. Available data only goes as far as 2018-2019 reporting but presumably will be updated in time.

Sustainable procurement guidelines and best practice

|

Australian Govt Sustainable Procurement Guide While the Australian Government Sustainable Procurement Guidelines are aimed at government entities, they provide private industry sectors insight into government procurement practices and goals which can assist in the tendering for and execution of government work. They also serve as good practice guidelines for private industry tenders and procurement. The site also contains useful resources for sustainable procurement such as a list of goods and materials comprised either entirely or partly of recycled materials covering everything from building, landscaping and construction materials to office fit-out and supplies. Additional links can also assist with finding suppliers for these materials and items. |

|

ARRB Recycled Materials best practice report Transportation networks offer a huge opportunity for the use of recycled content. While principally these networks sit under the purview of government entities this is not exclusive. Private industry also has the opportunity to utilise recycled materials within internal site boundaries. Property developments, industrial hubs and mining developments could be significant users if their procurement practices outlined the use of alternative content. This ties in with the sustainable procurement guidelines mentioned above. In June 2022 the Australian Road Research Board issued its final report into the use of recycled materials in road and rail infrastructure. The report provides a technical examination of the application and uses of recycled materials; emerging opportunities; comparative performance to virgin materials; market maturity; supply; and estimated recycled content potential. |

|

It considers the use of Construction and Demolition waste, Recycled Crushed Glass, Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement, Crumb Rubber, Blast Furnace Slag, Fly Ash, Bottom Ash, Recycled Solid Organics, Recycled Ballast and Recycled Plastics. This report shows that there are many different types of widely used recycled materials and that there is ample opportunity to increase the quantities and frequency that they are used across numerous applications. It also covers emerging recycled materials technologies that have significant opportunities for increased uptake. The AARB report is split into two parts which can be found here. |

|

Aspire – Waste matching services

ASPIRE is an online matchmaking tool for material resource exchanges. The tool allows companies that may have otherwise treated used products or waste streams that would otherwise have been discarded to find other companies that view these waste streams as a resource, thereby exchanging value. As the saying goes “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure”.

Numerous case studies are highlighting the many and varied ways their 1000 odd participating businesses have reduced costs associated with waste disposal, created economic benefits through a new revenue stream and saved on greenhouse gas emissions through localised reuse, re-purpose, and recycle solutions.

Poignant topics include:

Consideration of Carbon Lifecycle in recycling and circular economy efforts

A particularly interesting theme revolved around how little the greenhouse gas emissions featured in waste management metrics. Metrics and KPIs have tended to be focused on tonnages removed from landfill, or tonnages recycled rather than around the creation or avoidance of greenhouse gas emissions, measured in particular by ‘carbon dioxide equivalent’ or CO2e. This refers to not merely how much carbon is produced or reduced through improved primary practices, such as methane capture from water treatment plants and landfills, but how much CO2e is avoided through resource recovery and reuse, that is, if it is being reused, what contributors to CO2e have been removed such as mining emissions, land clearing, raw product processing, etc.

There is a growing call to introduce carbon accounting into the metrics of waste management.

Waste Precincts

The creation of dedicated waste precincts holds the potential to maximise economies of scale and efficiencies in operations and minimise the impacts of logistical supply chain issues, particularly within regions outside of major population centres.

The creation of dedicated waste precincts holds the potential to maximise economies of scale and efficiencies in operations and minimise the impacts of logistical supply chain issues, particularly within regions outside of major population centres.

These centres, hubs and precincts incorporate multiple collection, processing recycling and repurposing operations such as receiving stations, processing operations, treatment plants, sorting centres and even energy from waste facilities, whether they be biogas, pyrolysis or thermal-based. There are no particular restrictions on the facilities that may collate within a particular precinct other than what works effectively and economically for a particular region.

The scale of these waste hubs would also lend themselves to being located close to but outside of residential areas thereby minimising the ‘not in my backyard’ effect.

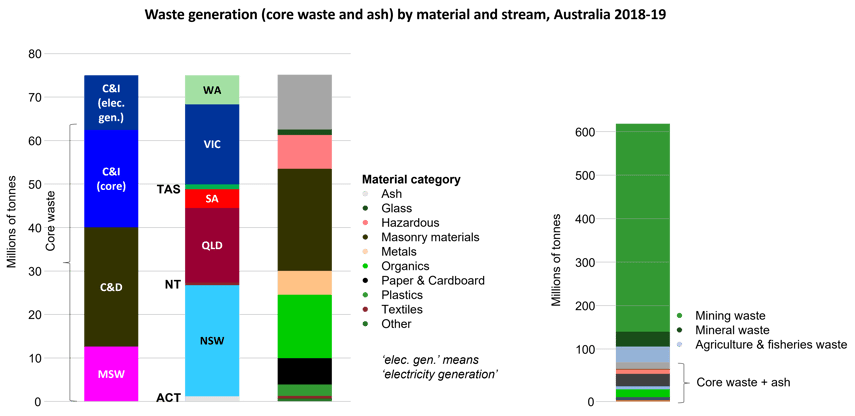

Mining Waste

When most people think of waste management, they think in terms of the waste generated by households, and community focused businesses, whether it be hotels, builders, restaurants, office spaces ~

However, the scale of contribution to Australia’s waste volumes generated by mining is staggering.

General waste – municipal waste, construction and demolition, and commercial and industrial sits around 75 million tonnes per annum. Mineral processing and agricultural wastes sit around 20 million tonnes each, however, mining waste equates to circa 500 million tonnes. This means mining waste represents around 80% of all of Australia’s waste, dwarfing all other waste streams.

Improvements in mining technology and market changes have made tailings and waste rock reprocessing more viable, which is reducing the waste stockpiles and extracting additional value.

However, there will be a limit to how far these technologies and methods can go. There will still be huge amounts of leftover reprocessed material. Instead of placing the remnant material back in tailings dams or waste rock piles and pits, Australia should be looking for better ways to recover this material as a resource. This initiative buys straight back into the use of the materials in construction, in line with the principles of the ARRB Recycled Materials best practice report and the Sustainable Procurement Guidelines mentioned earlier.

Of course, legislation will also play its part in supporting and enabling this move, however, there are already a limited number of successful examples of this being undertaken by some miners as they recognise the potential for additional income streams outside their primary mineral production – and all of this serves as good Environmental Social Governance (ESG) methodology. [more about ESG in the mining sector]

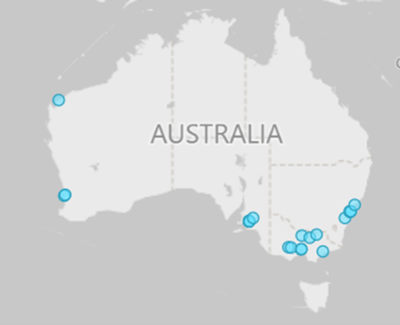

Energy Recovery

Whether it be small, household scale, behind-the-meter commercial applications, or large-scale base-load power supply, and be it from biogas, pyrolysis or thermal technologies expanding the country’s use of renewable energy from waste technologies should be taking a higher priority.

While in some areas these technologies may best suit behind-the-meter applications, and supplement gas usage, in large population centres or centralised municipal waste hubs these technologies hold massive potential to supply base load power which is becoming more critical considering the instability of the electricity network and energy prices of late, not to mention the gradual but imminent shutdown of all coal-fired power stations.

This image shows the number and location of energy from waste facilities across the country as of 2019 and includes Anaerobic digestors, Refuse Derived Fuel Facilities and Thermal waste facilities.

NSW, Vic, SA and WA all have facilities, with Vic having the most and the other states a couple of a few at most, but QLD, NT and TAS have none.

Unlike solar wind and wave technologies, renewable energy from waste facilities has the potential to provide controlled, steady and predictable baseload power. These facilities are prolific in parts of Europe but in Australia, their adoption has been slow and meagre. Some facilities can also produce multiple products not just energy.

[EFW facilities in Australia: National Waste Data Viewer]

The employment of these technologies, particularly where there are no further or better uses for waste materials, whether that be because they are uneconomical or the resource no longer has a better purpose, also fits well within the waste recovery hierarchy.

In summarythe benefits of a circular economy:

|

Leave us your details to receive future information on Siecap services: